The morning of May 12th I awoke to the smell of smoke in the air, that pleasant sitting-around-a-campfire smell. At daybreak, I could also see it, hovering over the ground like a thin, dirty-white veil, wrapping my house and everything on the valley slope as it slowly rose to meet the forest.

The feature photo was taken that morning from the valley floor, looking toward my neighborhood and the forest, the smoke lingering near the ground in the cool morning air.

I wasn’t surprised by the smoke because the day before, after the boys and I finished our early-morning run in the forest above my house and were driving out, I saw a large collection of Forest Service vehicles in what is otherwise a wintertime snowmobile parking lot at the edge of the forest. A group meeting was underway, a circle of women and men standing in the dirt lot. They were preparing to set a “prescribed burn” in the forest.

Anyone living near a national forest, especially in the West, has become intimately acquainted in recent years with the concept of “controlled” burning, or “prescribed burns” as a forest management tactic.

Here is how the Payette National Forest announced and explains the need for this spring’s round of burning on the InciWeb site, noting the number of acres to burn in various districts within the forest :

PRESCRIBED FIRE – Promoting fire-adapted communities and resilient landscapes

The Payette National Forest will be conducting multiple prescribed fires this spring. Depending on weather conditions burns could take place anytime from late March to early June. These prescribed fires reduce surface fuels, increase height of the canopy, reduce small tree densities, and promote fire resilient trees, thereby improving our ability to protect communities from wildfire. Additionally, these fires improve wildlife habitat, promote long-term ecosystem integrity and sustainability by reducing the risk of high-severity wildland fire. Prescribed fire is an important component of natural resource management and part of the comprehensive fire management program on the Payette National Forest.

The Council Ranger District plans to apply fire to approximately 5,000 acres in the Weasel project area (13 miles northwest of Council, and 3,500 acres in Mill Creek-Council Mountain project area (5 miles northeast of Council).

The Weiser Ranger District plans to apply fire to approximately 1,200 acres in the Robinson project area (22 miles north of Weiser).

The New Meadows Ranger District plans to burn approximately 3,000 acres in Boulder Creek (13 miles northwest of New Meadows): 103 acres in the Muddy Squirrel project area 9 miles northwest of New Meadows and 250 acres in the Meadows Slope project area. (3 miles northeast of New Meadows).

The McCall Ranger District plans to burn 350 acres in the Bear Basin area and West Face parking lot. (3 miles northwest of McCall).

The Krassel Ranger District plans to apply fire to approximately 5,500 acres within the Bald Hill project area (west and east of Yellow Pine); 3,800 acres in the Four Mile project area along the South Fork of the Salmon River near Reed Ranch and Poverty Flat camp ground (Approximately 18 miles east of McCall); and 70 acres around Krassel Work Center.

Trail heads and roads that lead into these areas will be posted with caution signs and a map of the prescribed burn locations. Fire personnel will work closely with the Idaho/Montana Airshed Group, the National Weather Service, and the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality to ensure that smoke impacts are minimized. The decision to ignite on any given day will depend on favorable weather conditions and the need to reduce smoke effects as much as possible. Smoke from these prescribed fires will be much less than what would be expected from a wildfire. If smoke concentrations approach air quality standards fire ignition may be delayed until air quality improves. Residual smoke may be visible for up to 2 weeks following ignition, but most of the smoke from the fires is anticipated to dissipate 1-2 days after ignition.

The Payette is approximately 2.3 million acres in size, so these prescribed burns, relatively speaking, are very small.

And if prescribed burns help prevent larger wildfires, I’m all in.

Too often since moving here in 2005 I’ve seen the enormous plumes of smoke from large wildfires on the Payette, rising fast and impossibly high in the sky, looking just like the plume of ash I witnessed when Mt St. Helens erupted in 1980. Eventually the wind disperses the smoke until it covers an entire landscape for miles around for weeks on end. Air quality is hazardous at times, and the smoke impossible to avoid.

August 21, 2015

August 26, 2015

August 26, 2015

The Teepee Springs Fire was the one that burned closest to my home, starting five-to-ten miles due north as the raven flies. For the first time, I attended evacuation information meetings hosted by Forest Service personnel, making the danger all the more real. That fire burned northeastward, away from me, but caused evacuations of nearby communities. As with many late-season wildfires, it kept burning to some extent until early winter rain and snow finally put it out.

Two years ago, in May, I noticed what appeared to be a new trail in a section of forest near my home where my dogs and I often hike. But it went straight up a steep hillside; a trail would normally climb such a slope via switchbacks. That’s when I realized it was a firebreak – a gap in vegetation or other combustible material that acts as a barrier to slow or stop the progress of a wildfire – in preparation for another prescribed burn. A few days later, from my house I saw smoke rising between the trees in that section of forest. The next time the boys and I hiked through there, in June, some hot spots were still smoldering.

Conall climbing the steep firebreak, May 9, 2019.

Smoldering stump, June 19, 2019.

Remains of prescribed burn, June 19, 2019.

It’s not unusual to be driving somewhere and see smoke rising from the forest. The Forest Service does a good job of alerting motorists, residents and tourists that they’ll see smoke from prescribed burns with signage on roads and posts on social media. Still, I’m sure they get tons of calls from people fearing the smoke is from a new wildfire.

During the past few days of runs and hikes on forest trails with the boys, I’ve pondered the strange mingling of two primary signs of springtime in the forest: blooms (wildflowers), and burns. New life, and fiery death.

Yesterday it was just me and Conall, running on dirt trails where only a month ago we were running on snow. As we started out just before 8:00 am a Forest Service fire engine truck drove into the big lot (another snowmobile access point) and parked. Checking the sign board at the trailhead I saw the map showing where this particular prescribed burn would occur. It included the trails I wanted to run. Based on my observations the previous day, I knew that the crew wouldn’t get started with actual burning until after 10:00 am, so off Conall and I went for our run of roughly 90 minutes. (Plus, they don’t ever close an area to use during these prescribed burns, they just warn that burning and smoke will be occurring.)

The wildflowers were amazing.

At one point during our run, on a section of trail heading north, I noticed red flagging on tree branches alongside the trail. This was new. I wasn’t sure of its meaning. Then, at a point where the trail curves westward and down toward the parking area, I saw a new firebreak, continuing north, with more flagging along its edges. Just as I’d seen in 2019, in preparation for the prescribed burning that was about to start, a portion of the existing trail within the prescribed burn area had been flagged as part of the overall firebreak.

Where trail and firebreak meet.

New firebreak.

When Conall and I finished our run, the Forest Service fire crews had all arrived with their vehicles and were holding their meeting in the parking lot, exactly as I’d observed the day before prior to the prescribed burn near my house.

It will be a few days before the boys and I run in this area, giving the smoldering stumps and logs a chance to cool so no dog pads are burned, although the torching is very specific and in this area, mostly small piles of tree debris from thinning of low branches over the last two summers. The trails themselves never show evidence of burning.

That evening I watched as some of the smoke from the burn near my house settled in the valley, seemingly following a creek that runs out of the forest across the valley floor to meet a small river that eventually drains into the Salmon River.

This morning the air was clear, so the boys and I ventured into the forest where they burned two days ago. Rounding a curve just a quarter mile up the hill I was surprised to see that they’d burned right to the edge of the road. Lots of smoke was beginning to rise after being kept low to the ground by cold overnight temperatures.

I drove a mile up the road to one of our favorite places to run and hike because the old logging roads are blocked by a gate. When we started our hike, the air was clear and the wildflowers were beautiful.

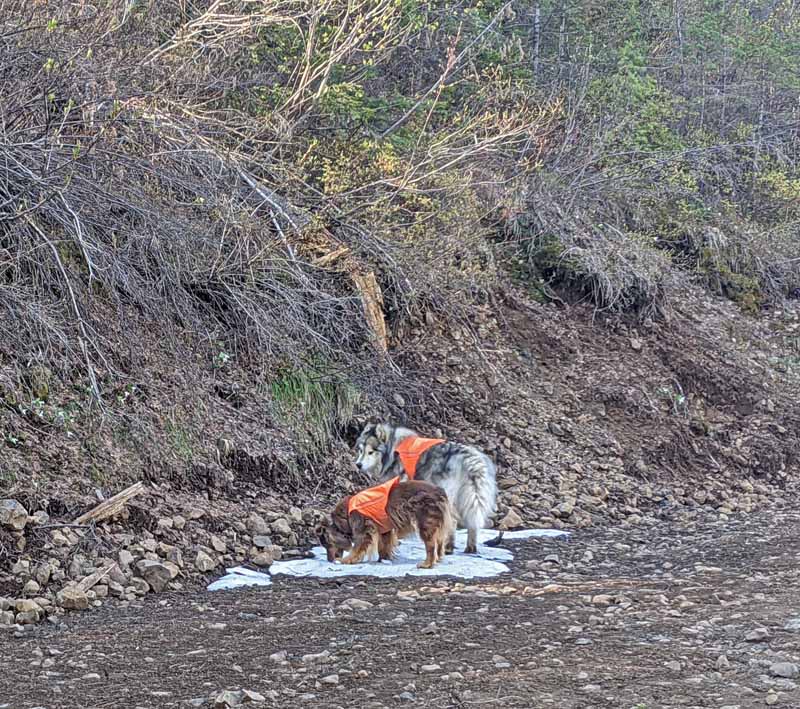

The boys even found a small patch of snow to enjoy, taking several bites to slake their thirst.

As we got closer to the gate and car, it was clear that the warming temperatures were helping the smoke rise. Now I could smell and see it.

I can’t help having conflicting feelings as I watch the smoke rise from prescribed burns, see the smouldering stumps, downed branches and logs, the blackened trunks of healthy trees with black soil around their roots. I fully accept and believe in the science that shows these strategic burns make forests healthier in the long run and in the short term my well prevent a devastating wildfire from getting completely out of control.

I worry about the displacement of wildlife, even if just temporarily.

But mostly, I hate the smoke. Especially knowing how damaging the particles are to lung tissue. Most prescribed burns occur in the spring, when the ground and vegetation is still moist enough to keep the burns controlled. Yet when the burns occur so close to home, like this spring, it begins to feel like fire season is April through October and we rarely get a break from the smoke.

Yet another reason I’m looking forward to moving to Vermont. They have wildfires there, too, but nothing like what the West is experiencing.

Until then, I will continue to focus on the wildflower blooms at my feet – the happy beauties of the forest – and accept the blackened scars of prescribed fire as a necessary part of the forest’s ecological health and life cycle.

The smoke is the worst. And the interaction with the pandemic is definitely bad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting post re controlled burning, something we do not have here. Some (all) of those ground flowers are beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank goodness it was only a prescribed burn. I worried it was another wild fire. In my country, we do not experience wild fires but we have bad typhoons. The wild flowers are so beautiful. Thank you for sharing them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your comment about typhoons is a good reminder that every location has some potential disaster looming. So much better to focus on the here and now and nature’s beauty than worry about the next natural disaster!

LikeLike

The park service has been using prescribed burns to control the brush growing in the open plains of the Gburg Battlefield. I appreciate this because I find the tangle of the thicket pretty ugly to look at but the burnt smell lasts for weeks afterwards. A big forest-fire burn in the shadow of my house would make me pretty nervous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, once you see the end result – sometimes not obvious for a year or two – you realize the burns make sense. Indigenous cultures often used controlled burns. But the smoke? If it were ONLY the smoke of prescribed burns in spring I wouldn’t whine, but then we get the wildfires in the forest during the summer that put so much smoke in the air, often for weeks on end. We used to refer to “dirty August” because that’s when most of the wildfires occurred, but now it’s more like “dirty summer and fall.” I’m looking forward to breathing easier (literally and figuratively) in Vermont.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I cannot imagine the smoke involved with these fires, oh me goodness no.

As for the term prescribed burn, I had not heard of that one before, only the controlled burn term. But I guess it does all make sense in the grand scheme. But you are correcto, the smoke just plain sucks.

Those boys are living their best lives, aren’t they? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Smoke sucks, indeed.

And yes, my number one job is making sure my boys have the best possible life. When I die, I want to come back as one of my dogs 🙂 Oh, wait…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ugh!

Haha! I want to come back as one of my cats . . . umm, yeah . . oh wait . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wildfires must be terrifying, so I can understand them doing what they can to stop them, but I wouldn’t like to live with that smoke either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s the trade-off: burning and smoke in small, planned doses now, in the hope of averting an uncontrolled wildfire with blankets of smoke later. I’m all in on trying to mitigate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is definitely science to these prescribed burns and hopefully they help prevent the forest fires that are becoming more normal than an anomaly. Hopefully you and the boys will be back on your favourite trails soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good description of prescribed burns. A lot of people don’t understand the purpose of the controlled fires. Have you ever read The Big Burn by Timothy Egan? I highly recommend it. The gigantic fire in 1910 occurred partly as a result of suppressing fires. Too much fuel! Lovely wildflowers near your place, Rebecca.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Siobhan. Prescribed burns are controversial, and I understand why, but I embrace the science behind them and approve. I do have The Big Burn on my Kindle but have yet to read it, despite being an Egan fan. Probably the perfect time to read it – thanks for the nudge!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] last post described the twin events of spring in the forests of Idaho’s central mountains: blooming […]

LikeLike