If you spend time in the outdoors, eventually something will go wrong. It’s a law of nature. But if you survive, those epic failures become the best stories! We’ve all read about amazing accomplishments in the wild, but now it’s time to tell us about the not-so-great times and what you learned from them. Share your best #EpicTrailFail stories on your own page, include this paragraph as a header, and then provide a link in the comments here or here. We’ll curate and circulate the best stories in future posts. We can’t wait to read about what you’ve survived!

Arionis of Just A Small Cog and Rebecca of Wild Sensibility.

My Most #EpicTrailFail

A little background: I belong to group of compulsive endurance athletes known as ultra-distance trail runners, although these days I’m “retired” from the long distance stuff. An ultra is an event of any distance longer than a marathon. Ultra races are typically 50K (31 miles), 50M, 100K or 100 miles in length, usually on mountainous trails, and take hours or even days to complete. Between 1990 and 2005, I competed in close to a hundred marathons and ultras, but the trail runs that form my fondest memories are the non-race adventures such as running the Inca Trail in Peru and around Mt. Rainier on the Wonderland Trail.

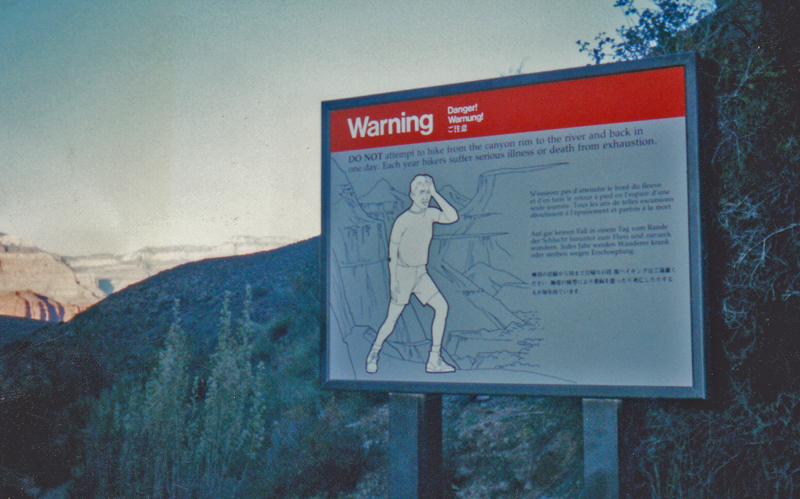

The most spectacular adventure run of all, for me, is the double crossing of the Grand Canyon, a trek of 42 – 46 miles depending on route. Named the Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim (R2R2R), one runs from the South Rim to the North Rim and back again, with a total elevation change of 22,000 feet. Not a simple undertaking, given the distance, elevation drops and gains, extreme temperature variance—from snow and freezing temperatures on the rims to 90F-plus at Phantom Ranch on the river—and lack of easy water sources.

In the mid-90s several ultra runners from around the country would congregate at the South Rim on the first weekend in November for a double crossing, after the official tourist season has ended and there are fewer people and mules (and less mule piss and poop) on the South Rim trails. In 1996, my first R2R2R attempt, I had an amazing run, finishing in around thirteen hours. My second attempt in 1997, however, did not go as planned.

Some days, nothing goes right, and other days, everything goes wrong.

***

My small group of four drops off the South Rim and starts running down the South Kaibab trail at 6:00 AM on a fine, cold November morning. It’s still dark, so for the first mile or two we use our flashlights to avoid sliding off the icy edges of the steep early section of trail. Soon we’re rewarded with a spectacular sunrise, fiery light reflecting off the canyon walls.

Our run begins with 6.5 miles of relentless, steep downhill, dropping 5,000 feet to the Colorado River. We’re excited and energized, avoiding the temptation to race down the hills in order to save our legs for the rest of the day. Along the way I stop for a photograph with a young bighorn sheep standing just feet off the trail.

Pretending to offer a treat to the sheep.

Poor sheep thought I was serious!

After the long descent we cross the Colorado on a suspension bridge, passing through Phantom Ranch before starting up the North Kaibab trail toward the North Rim. We encounter another runner coming down who informs us that the two usual sources of piped water along the North Kaibab trail are broken. This is unanticipated and very bad news. We now realize we have to carry enough water in our running packs to get us up the 14 miles and 6000 feet to the North Rim and the return trip back down to Phantom Ranch. There will be no water at the North Rim, as it’s closed for the season. Luckily, on the way up we spot a small stream near Cottonwood campground, about halfway between the river and the North Rim. We top off our pack bladders, relieved to find some water on the north side.

The run continues to go well. It’s impossible to not be awed by the scenery and the various colors of the rock as you travel through 1.7 billion years of sedimentary layers from river to rim. I reach the North Rim feeling overheated but otherwise good, and turn to head back down the trail with my boyfriend; other friends are ahead or behind us. After refilling our water bladders at the Cottonwood stream, my boyfriend goes on ahead, at my urging. He’s faster, and I enjoy running on my own, feeling that the best way to take in the splendor of the Canyon is to move as silently as possible, alone and aware.

Photo at left: heading up to the North Rim, still smiling but feeling the heat.

Soon, though, my right quadriceps muscle starts talking to me. The complaining gets louder as I continue downhill, until eventually I have to listen to the pain and walk—with a limp—rather than run. I know that the cramping is the result of dehydration from conserving water during the climb to the North Rim coupled with running too hard on the way back down, all during the hottest part of the day. Heat is my running nemesis. The temperature gauge reads 90F at Cottonwood on our way back down from the North Rim.

But hey, I’m not worried; I’m about two-thirds of the way through the run at this point, and figure I can walk the remaining five miles to Phantom Ranch, then hike up to the South Rim. Everyone hikes those last miles as it’s simply too steep a climb for any but the strongest athlete to run at the end of a double crossing. I finished Western States 100 in 1993 in a similar over-heated and dehydrated condition, walking the last 15 miles, with nausea, so this is not unfamiliar territory.

Soon I come upon a father and two kids sitting beside the trail watching some deer. I stop to chat, any excuse to rest my quad. I must look a mess, because the father asks me, “Are you OK?” When I hesitate to answer, he gives me a look of pity and offers me a bunk in the cabin he’s sharing with a bunch of kids at Phantom, “…if you need it.” Telling him I’ll give his offer serious consideration, I limp on down the trail. Within minutes, he and the kids pass me, which drives home just how slowly I’m moving. The father repeats his offer of a bunk. I thank him again, but brush it off. When I finally make it to Phantom, he waves from where he’s sitting in front of his cabin so I’ll know which one it is. But my running friends will go nuts if I don’t arrive at the South Rim finish point as planned, no matter how late, so I tell the man I’m determined to go on. “But don’t be shocked if I change my mind and turn up later in the night,” I say with a weak laugh as I leave him with my own wave.

I rest at Phantom for a few more minutes, eating a bagel with peanut butter for energy. I leave at 4:45 PM, ten hours and 45 minutes after I started this journey, way behind schedule. All of my runner friends have already passed me. To their credit, they all asked if I needed anything and offered to stay with me, but I assured them I’m fine. In truth, I’m pissed at myself for getting dehydrated and don’t want to ruin their run just to baby-sit me. Besides, the only alternative to using your own power to hike out is to get a very expensive helicopter ride. I’m determined to get out under my own power.

I can’t remember what time to expect sundown, but I do remember that the previous year it took me three hours to climb out the shorter, 6.5-mile South Kaibab Trail. This year my small group of four agreed to go up the nine-mile Bright Angel Trail, longer but less steep as it gains 5,000 feet to the rim. It’s going to take me a long time, finishing well after dark. My tired brain isn’t up to calculating just how long, but I’m confident I’ll be fine because I have my flashlight with me. Also, I know that Bright Angel Trail has a campground half way up, Indian Gardens, with water available. And people. I remind myself of the ultra runner’s mantra: relentless forward progress, one foot in front of the other.

As the day finally cools and with some food in my stomach, I leave Phantom, crossing the Colorado on the smaller hiker’s bridge, following the trail along the river. Suddenly, I start belching, and that peanut butter bagel I just ate comes back up. Clearly, I’m more dehydrated than I thought. My stomach won’t tolerate food. At least I’m able to steadily sip water from my pack’s bladder. Still, I know my situation is grim, many tough miles ahead on an empty stomach.

After a mile along the river the trail turns upward and becomes more difficult. By now my right leg is very painful because of the cramping and strained quad, especially when stepping uphill onto the many annoying water bars set into the trail. I need a walking stick to relieve some of the strain on my quad, but can’t find anything in this arid, desolate landscape devoid of trees. I finally break a branch off of some low-growing shrub; it makes a crude bent walking stick, with thorns, but allows me to keep moving with less pain.

I try to calculate my miles-per-hour pace, but there are no mile markers on these trails. I figure I’m making two miles per hour – painfully slow. Admitting to myself it’s going to be a long night, I panic a bit, remembering that my flashlight batteries at best only last four hours and I had already used them for about 30 minutes at the start of the run. Last year I didn’t need a flashlight on the way out, finishing before dark. This time, I still have over seven miles to go with darkness falling fast.

I know the campground is four miles up from the river; that becomes my immediate goal. I go as long as I can without using my flashlight, but there’s only a new moon for light and eventually it’s truly dark. After tripping several times, I have to use my flashlight. Once I do, I actually pick up the pace significantly.

When I finally arrive at the campground, I accost the first person I see in my flashlight beam and ask for any spare AA batteries they might have. The woman takes me to her campsite and her boyfriend gives me some of his batteries, but warns he doesn’t know how much power they have left. I gratefully accept his batteries while politely declining the couple’s offer to let me stay there overnight.

As the woman escorts me back to the trail, she happens to mention that there are two emergency shelters between the campground and the rim – one three miles below the rim, and the other 1.5 miles – and they both have emergency phones. This is excellent news! My new goal is to continue upward as long as I have flashlight power, stopping at one of the shelters if I have to. It’s getting late enough that I know my running friends will start to wonder what has happened to me, and before long they’ll send their own search party down the trail. The higher I get, the less distance they’ll have to come down to find me; they’ve already done their own R2R2R that day. The absolute last thing I want is for the park service to mount a search. I don’t want to be one of those people who have to be rescued.

I flounder on up the trail. About a half mile after leaving the campground, my original flashlight batteries go dead. Without warning. I instantly go from light to no light. Sitting in the middle of the trail, I change batteries in total darkness. The four AA batteries have to go into the small diver’s light just so; I get it right on the second try. That task accomplished, I feel a sense of calm. It’s an incredibly beautiful night, with clear skies and more stars than I’ve ever seen. I soak in the view, the quiet and solitude. It’s a cool night, but not cold and I’ve got a jacket, hat and gloves in my pack. And despite being nauseous and unable to eat, my attitude is good. I have plenty of energy for this slow hiking, which I attribute to being in such a special, spiritual place, experiencing the Grand Canyon in ways I never anticipated.

Eventually I stand up and continue up the trail, using the “new” batteries that I realize can die on me at any time, adding another element of risk to this nighttime hike. Worrying about my friends being worried about me, I keep limping upward at a slow but steady pace, a bit faster than before.

Eventually I reach the emergency shelter three miles from the rim, located a short distance off the trail. I pass it by. A mile and a half later, I spot the sign for the last shelter before the rim, this one a bit removed, not as obvious as the one before. I continue on, but after some muddled thought, I acknowledge that I’m relying on dicey batteries and am now high enough in the canyon that the drops off the side of the trail are steep and long. I’m glad I can’t actually see them in the dark; there’s just a black void on one side. I’m acutely aware just how dangerous a misstep can be; I don’t want to even think about negotiating this portion of trail without a working flashlight. Nor do I want to have to sit in the middle of the trail for several hours, awaiting daylight; there are scorpions here. I turn back down the trail and make my way to the shelter.

The shelter is a three-sided stone-and-wood structure with floor and roof, and benches built into walls that go roughly one-third from floor to ceiling, the rest open to the elements. It takes me a couple of minutes to find the shelter’s emergency phone, which is attached at the ceiling in a back corner, eight feet off the ground. I painfully scramble onto a bench, reach up and lift the phone off its cradle, connecting directly to the ranger station at the South Rim.

I tell the answering ranger that I’m fine and ask her to please let my friends know where I am and that I could use some fresh batteries. I hang up so she can try to reach them at the motel. The ranger calls back a few minutes later, saying no one answered at the room. She then tells me about a cache box hidden behind the shelter and gives me the combination (3333, for future reference), suggesting I take the flashlight stored there. I find the box, open it and find the flashlight, but ironically its batteries are dead. I find one spare battery (D cell) in the box and swap it for one of two in the shelter flashlight, but no luck. I call the ranger back. I mention the dead batteries. I tell her that I’ve found a comfy sleeping bag as well as some crackers and fruit juice in the cache box, I’m quite snug and happy, and will wait out the night in the shelter, hiking out in daylight. She doesn’t like this idea and says she’ll keep trying to call my friends.

I sit on the shelter’s bench, wrapped in the sleeping bag, nibbling on crackers. It’s nearly 11:00 PM. I listen to the night sounds – mostly crickets – feeling safe and peaceful, until I hear something scuffling just beyond the shelter wall. I grab my flashlight and aim it toward the sound. The beam hits the face of what appears to be a cross between a fox and a raccoon, its eyes glowing as it sits on the “window” ledge of the opposite wall. Staring back at me, unalarmed, the creature – whose big fluffy tail has rings around it – jumps down and moves around the shelter’s exterior, giving me one last casual look before moseying off. Turning my flashlight off, I begin to think about the other nocturnal creatures that inhabit the canyon, including cougars, and listen intently but still somehow briefly fall asleep. A few minutes later I jolt awake, chastising myself for dozing because I might not hear my friends coming down the trail looking for me. What if they walked right past the shelter? I work hard at staying awake, despite my exhaustion.

Fifteen minutes later, I do hear voices from up the trail. After wondering if I’m hallucinating, I recognize them – three of my friends coming to find me, chatting quite happily with each other. I’m rescued! I call out to them, and they follow my flashlight beam to the shelter. We hug and laugh. With my bit of rest, food and fluids, I actually feel pretty good. After returning the sleeping bag to the cache box, we head up the trail, me using a borrowed flashlight. I’m surprised at how well I’m able to hike the remaining three miles to the rim, no limp, my quad fine, no walking stick required. Making good time, we top out at ten minutes after midnight. I’ve been out a total of 18 hours, finishing six hours behind schedule.

The ranger never did reach my friends at the motel; they knew something was wrong and came looking for me on their own. I knew I could rely on my ultra running tribe to come to my aid – it’s one of the things I love about the sport and the people who participate in it: we look out for and take care of each other. They even had pizza waiting for me back at the motel.

While this was not the run I had in mind when I started out the previous morning, I must say that if one has to get into trouble on a trail, the Grand Canyon is a beautiful place to do it. I wasn’t worried about getting lost. I always had water and food in my pack, and spare clothing for warmth. My friends knew my route and when I was overdue. Strangers were kind and offered shelter. At the emergency shelter, I was completely safe and comfortable and could easily have spent the night there. (I sent the rangers a thank you note with some cash to replace the dead batteries and snacks in the cache box.) Many small things went wrong that day, including lack of water on the North Rim section, and heat, but the biggest error was simple and entirely my own: not having backup batteries for my flashlight. Four, tiny batteries that would have easily fit in my pack, weighing hardly anything.

I learned that the creature I caught in my flashlight beam at the shelter was a ring-tailed cat – apparently quite a rare thing to see. So, there’s that upside.

I finished the adventure with a story to tell, a new appreciation for my own limitations, and a hard-earned lesson to never assume that one success ensures a repeat. I learned that had I been patient and taken more time at Phantom to re-hydrate, eat and rest, my cramping quad would have recovered and my climb out of the canyon would have been much faster.

I also learned how spectacular it is to be in the Grand Canyon, alone, with a clear night sky full of stars.

I returned to run the Canyon again in 1998, but opted for an abbreviated route with a friend, starting at the South Rim as usual and crossing the river but turning back at Cottonwood, half-way up the North Rim. That way we were certain we would finish before dark. Even so, I carried two flashlights as well as spare batteries.

I always learn the most from my failures.

What has been your most #epictrailfail? What did you learn?

Photos: Feature photo by Linnaea Mallette, CC0/public domain. Unless otherwise noted, all other photos mine. In the mid-90s we tended to carry lightweight disposable Kodak cameras on these adventures and because prints were pricey, we didn’t take lots of photos, nor were they of great quality. I’m glad to have these few as mementos.

You did the rim to rim? Holy hell! That’s amazing. Of course it sounds grueling, painful and ridiculously difficult so I’m very glad I didn’t!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

What, you’re not a trail masochist? For shame, River!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am not.

And proud of it!!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

R2R (South to North) is a goal of mine. Next time we visit as a family, I’m hoping to make the “run.” Your’s was a fairly major fail and highlights my biggest concern about trail running. Making others worried while I’m not in any real danger, just lost or moving slowly. Even in these days of cell phones, many of the places I run have no coverage and I spend my whole run worried about making a wrong turn and getting lost. Or twisting an ankle. Or getting dehydrated and needing to wait it out. My #EpicTrailFail post isn’t a concise incident but rather the cumulative effect of simply never knowing where I’m going. https://jefftcann.com/2017/01/15/bad-ass/

LikeLiked by 3 people

OMG, “babywater” – too funny! Great story, Jeff. Getting lost is my worst nightmare. I’m blessed with a pretty good sense of direction, and a sort of sixth sense that tells me when I’m going the wrong way, making me stop and retrace steps before I’ve gotten too far off track. Plus, for the past 20 years or so, I’ve almost always had at least one Malamute running with me, and they have infallible senses of direction, always knowing exactly where the car is. As for bad ass, the only time anyone has called me that – during a trail running event in OR a few years ago – it was a 20-something who saw all my gray hair and clearly thought it was amazing someone so old was running the race 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

As I age, I increasingly believe the baddest badasses out there are the folk still doing this in their 60s. Suppose I could use a dog to get me back to my car. It can get pretty nerve-wracking all alone in a strange forest. It’s on my mind all the time. I have a short essay coming out in a magazine this month on this exact topic.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I hope you’ll link that article here when it’s published (and congrats on having your essay published)!

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s an ‘ink and paper’ magazine. Nothing to link. I’ll post it on my blog in January or February (depending on when the issue comes out). The magazine is called Like the Wind. It’s all running and published in London. I’m sure they would like some of your stuff. However they don’t pay, but where else are you going to publish running stuff? Even my best stuff has been rejected by trail runner. They don’t really want first person stuff anymore (unless you’re Jenn Shelton).

LikeLiked by 2 people

That was an awesome story! I could feel the excitement and the anxiety as if I was there with you. I never used to carry a headlamp when I went on day hikes, thinking I would never need it. Then for some reason I decided to throw one in my pack on a recent day hike and I’m glad I did. It saved my butt. I’ll write about that one eventually.

That was great first entry for our #EpicTrailFails series. Thanks again for working with me on this!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks, Ari. Some lessons are learned with more struggle than others! And thanks for collaborating with me – a fun project!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very awesome run. Here’s my little story… https://marthakennedy.blog/2019/12/03/trail-fail/

LikeLiked by 4 people

Great story! An epic fail of another sort – ouch! – with a laugh-out-loud ending. Well done, Martha!

LikeLiked by 3 people

I didn’t mean to press “send” but OH well. I love your story. It must have been a spectacular run and the “lesson” — that nature is the boss — I don’t think we humans can learn that often enough. Until I was 50 or so, I didn’t even know there was such a thing as people doing this thing you and your friends did. I don’t know if I would have had the ability, but I would like to have tried. I would have loved it, I think.

Hiking with big hairy dogs in the desert and chaparral, dehydration was always a big concern for me and I carried gallons of it. Life definitely improved for me with the advent of the hydration pack. Carrying all that water plus being an idiot about running downhills might have been one reason for my toasted knees, I don’t know. Probably just a fundamental anatomy fail. One of my favorite mountain hikes had a good well and I usually planned whatever route we took to hit that well a couple of times.

Once on the top of a “mountain” my friend and I ran into a group of kids who were bright red with pale lips and seriously overheated. We offered them water then we noticed their full packs. “What’s in your packs?” my friend asked.

“Rocks.”

“Rocks?”

“Yeah, we’re training for Whitney.”

“Why didn’t you load up with water. It’s heavy.”

“Yeah but we would have drunk it and then our packs would be too light.”

All around us were rocks. “Next time bring water, drink your water, put rocks in your pack to replace the weight. People die of dehydration.”

“Wow, dude.”

LikeLiked by 5 people

Water is life. Dehydration sucks. Like you, when I take my dogs for runs, I make sure there are water sources along the way, and if I’m not sure, I’ll carry some for them. Luckily where I live, water is plentiful. The rocks-in-packs story is hilarious! I hope they learned the easy lesson, from you, rather than a hard lesson from Boss Nature.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Boss Nature doesn’t always see the funny side of things. 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a harrowing experience. These ultra marathons are really unbelievable, what with all the variables you have to take into account.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Here are two epic trail fails to choose from:

https://aunatural.org/2018/04/20/a-rainy-day/

https://aunatural.org/2019/08/26/the-great-adventure/

LikeLiked by 2 people

Those are epic fails, indeed! Thanks for sharing; great storytelling and photos! Love this line: “Just because you feel like dying is no reason not to appreciate beauty when you find it.” Exactly.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Such an adventure! I had a friend do R2R a couple years ago. Maybe someday I will try it too. We’ll see 🙂

LikeLiked by 3 people

Never say never, and secretly plan to do it so that it will feel like you’re letting yourself down if you don’t 🙂 You won’t regret it, even if things don’t go completely according to plan 😉

LikeLiked by 3 people

Did you ever do the Badwater to Whitney Portal run?

When I was younger I could easily run a few miles but anything over about 10K started to look daunting. Probably more psychology than anything else. Maybe 20 years ago I ran the Bay to Breakers. Since then I walk it. My knees are completely fried. For that matter, so are all my other joints. I live by Ibuprofen pills and cortisone shots.

I’ve had a couple of other #epicfails.

Like the time I was rock climbing in the Sespe Gorge by Tar Creek (back when you could still go there) in bare – well – everything. You can really mess up your feet on decomposing granite. Even if you aren’t wearing anything else, you need to wear shoes. Eventually went to the ER and I had to use a walker for weeks. My wife was not amused. It was then I got the aforementioned SPOT communicator.

Another time I hiked out an easy 10 miles with my dog Avery and turned back to discover the trail wasn’t there anymore. Just a very steep scree slope that looked like it might give if I looked at it too hard. I was a bit more risk-averse then than I was 20 years ago and decided that discretion was the better part of valor. Fortunately, I had a SPOT communicator and I texted my wife what had happened. When The Ventura County SAR helicopter showed up they said they’d been told by my wife that I was lost.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m giggling, thinking about what the ER staff had to say after your visit for your climbing injuries 🙂 Your wife is clearly a very patient and understanding person. It seems that living life fully means having a few epic fails along the way, along with several minor ones. A sense of humor after the fact is essential. Nothing ventured, nothing gained, right? I’m sure there’s a book here somewhere…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Or at least a few blog posts

LikeLiked by 2 people

thank you for sharing

LikeLiked by 3 people